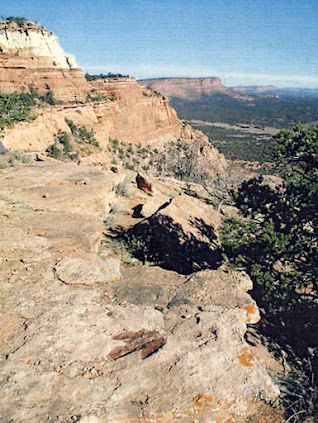

Flag Point track site, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Internet photo public domain.

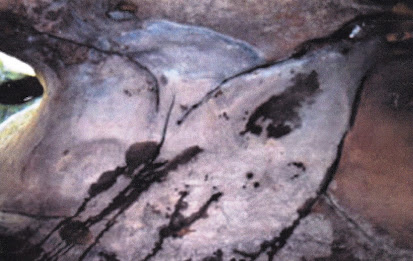

Painted track at Flag Point track site, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Internet photo public domain.

Chirotherium track, Joseph City, New Mexico. Photograph from Mayor and Sergeant, 2001.

Petroglyph of chirotherium track, Joseph City, New Mexico. Photograph from Mayor and Sergeant, 2001.

I think

that my two favorite things in the world may be rock art and dinosaur tracks.

And I would imagine that we all know about the red pictograph of the nearby

dinosaur track at Flag Point in Grand Staircase – Escalante National Monument

in Utah. RockArtBlog published a column about that marvel on 21 November 2015

in a column titled “A Painted Dinosaur Track in Utah.” Also, on 13 June 2014 I

wrote a column titled “A Dinosaur Track Petroglyph” on a report by Adrienne

Mayor and William Sarjeant of a petroglyph they believe was inspired by a

nearby dinosaur track. Now, I have seen a report about a site in Lesotho, a

sovereign enclave in South Africa, painted by a San bushman a artist that not

only records a dinosaur track, but apparently includes a couple of images of

the creature that the artist imagined to have made the track (Helm et al. 2012)

Mokhali Cave, Lesotho. Photograph Helm et al. Fig. 3.

The

pictographs at this site were first recorded by one Paul Ellenberger, the son

and grandsonof two generations of missionaries and ministers in Lesotho. “Swiss-born D.

Frédéric Ellenberger (1835-1910) came to Lesotho in 1861. He spent the next 44

years in this work, first in Morija and then in Masitise, where he created

temporary accommodation by building a stone wall in front of a massive rock

overhang. He lived with his family in this Cave House for 13 years.” (Helm

et al. 2012) One of Ellenberger’s children, Victor, later visited the site with

his own son, Paul, who recorded the pictographs. “Victor Ellenberger (1879-1972)

was born in this Cave House while a war raged outside. He excelled as a student

and went to France for his secondary education, then worked as a minister from

1917 to 1934 in Lesotho (mainly at Leribe) and then in Paris. He became an

expert on Lesotho’s flowering plants, changing environmental conditions and the

tragic end of the San, and published books on these topics. With the help of

his son Paul he copied over 400 San paintings.” (Helm et al. 2012)

San painted track image, Photograph Helm et al. Fig. 4.

Victor and

Paul visited the site accompanied by Frederic Christol (1850-1933), a Lutheran

minister and artist. “Armed with this knowledge of the

Ellenbergers, we can imagine a 1930 visit to a rock overhang 10 km north-east

of Leribe (Hlotse) known as Mokhali Cave. Victor was the minister in Leribe and

likely the orchestrator. Present were Victor’s father-in-law, the artist

Christol, and 12-year-old Paul, who was given the task of tracing the paintings.

While his grandfather sketched the cave, Paul traced the wonderful images,

which were unlike anything he or his father had seen before. Beside a painting

in red ochre of a three-toed dinosaur footprint, there were three graceful

figures of the imagined track-maker.” (Helm et al. 2012) Since the

footprint is three-toed made by an ornithopod, the San artist had recognized

its resemblance to a bird track and created the three imaginary figures which

are very birdlike.

San painted track image enhanced, Photograph Helm et al. Fig. 5.

As is so often the case, the original

drawings had been filed away and essentially forgotten. “The tracings had languished in obscurity in Lesotho and then in

Montpellier (Montpellier University in France). But in 1989 David Mossman, a Canadian paleontologist on sabbatical in

France, met Ellenberger and learned about them. In 2004 he lectured in South

Africa and visited Mokhali Cave with his son Alex. They located it after an

exhaustive two-day search, finally identifying it with the use of a copy of

Christol’s sketch. Unfortunately the paintings had faded badly – the footprint

(resembling that of an ornithopod) was just discernible, but the track-maker

images were no longer visible. Ellenberger and the Mossmans then collaborated

with renowned ichnologist Martin Lockley in submitting the article to Ichnos.” (Helm et al. 2012)

The claim by Ellenberger et al. (2005)

that the track-maker images predate European attempts was based on the estimated

latest possible occupation of Mokhali Cave by the San (1810-20), before it was

occupied by the son of the Basotho king and before the San were killed or

driven from the region. Implicit in such an estimate is the possibility that

they may have been made even earlier. This report assumes that the San were the artists. (Helm et al. 2012)

Drawing of San painted track image and imagined track makers, image courtesy David Mossman, from Helm et al. Fig. 2.

“Employing

technologies developed in astronomy, forensics and medicine, and applying them

specifically to rock art, Kevin Crause has developed the CPED Toolset –

Capture, Processing, Enhancement, Display. After obtaining high-resolution

images, data is colour-balanced and processed to remove lens distortion.

Designed enhancement algorithms resolve imagery details that cannot be resolved

under normal light conditions as perceived by the human visual system. By using

this technology, images often result of rock art that are no longer visible to

the naked eye. We wondered what the CPED Toolset could offer regarding the

faded footprint and track-maker images. Kevin and Charles Helm revisited

Mokhali Cave to test this in 2011. The cave, which we found without difficulty

thanks to excellent directions from the Mossmans, is 75 m wide, 10 m high and 5

m deep. It provides a magnificent north-facing view over the Caledon Valley and

its level floor is wide and deep enough to encourage habitation, as in

Christol’s sketch, which depicts three Basotho huts. However, it is exposed to

the elements. Northerly winds, winter snow and freeze-thaw events damage the

paintings on its walls, which are prone to flaking off. The chances of rock art

surviving seemed remote. However, the footprint, 2 m from the eastern end of

the cave, was recognizable. Midway along the floor were the remains of a

circular hut. In addition to analysing the footprint and surrounding area, all

promising surfaces in the cave were photographed. This yielded a few images of

so-called Late White paintings by Bantu-speaking agriculturalists (Lewis-Williams

2006), likely representing Basotho rock art, but also suggesting the

possibility of Basotho artists creating the dinosaur images. Rock art shelters 200mfurther

east yielded numerous San paintings. In the valley of the Subeng Stream below,

3 km from Mokhali Cave, we visited a dinosaur tracksite that was recorded by

Ellenberger in the 1950s. From here Mokhali Cave was visible."

(Helm et al. 2012)

“Computer

programs have enhanced the image quality at this site, confirming the accuracy

of Paul Ellenberger’s 1930 tracing and the relation of the footprint to the

track-maker images. However, for details on the track-maker images, the efforts

over 80 years ago of a remarkable pre-teenager remain the sole source. Future

work is required to resolve the origin of this rock art and, if possible, its

age.” (Helm et al. 2012) This may be a reference to their CPED toolset

or possibly they finished it up with D-Stretch, in any case they now have

provided a great image of the painted footprint that was previously hard to see.

NOTE: Some images in this

posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain

photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I

apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will

contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read

the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Faris, Peter, 2015, A Painted Dinosaur Track in Utah, 21 November 2015,

rockartblog.blogspot.com.

Faris, Peter, 2014, A Dinosaur Track Petroglyph, 13 June 2014, rockartblog.blogspotcom.

Helm, Charles, Kevin Crause and

Richard McCrea,

2012, Mokhali Cave Revisited, Dinosaur

Rock Art in Lesotho, April 2012, The Digging Stick, Vol. 29, No. 1. Accessed

from Researchgate.net.

Mayor, Adrienne and William A. S. Serjeant, 2001, The Folklore of Footprints in Stone: From Classical Antiquity to the

Present, Ichnos, Vol. 8, No. 2, 143-163.

SECONDARY REFERENCES:

Ellenberger,

P, Mossman, DJ, Mossman, AD, & Lockley, MG. 2005. Bushmen cave

paintings of ornithopod dinosaurs: paleolithic trackers interpret Early Jurassic

footprints. Ichnos, Vol. 12 No. 3, 223-226.